A Well-Planned Pivot Pushes Arsenic Out of the Marketplace

“We recognized the perfect opportunity for action with the largest commercial use of arsenic in playground equipment. The operation of just a few target institutions that made and marketed the product containing arsenic had a huge consumer-based emotional liability, which was children at play are children at risk.” —Bill Walsh, Healthy Building Network

How do you reduce shipments of a known toxin by 80 per cent in less than two years? According to Bill Walsh, founder and president of the Board of Directors for the Healthy Building Network (HBN), you have to start by asking the right question. When Walsh began thinking about getting arsenic out of America’s homes, the toxics-reduction community was asking, “How can we strengthen the EPA regulatory regime to reduce arsenic in the environment?” Walsh asked, “Do you want healthy children?”

By reframing the task to be accomplished, Walsh shifted the battle lines from the corridors of the EPA onto the more promising ground of the Consumer Product Safety Commission, where public opinion can help define the common good.

In what would turn out to be HBN’s first of many victories, Bill Walsh and his colleagues involved in the Arsenic-Free Playgrounds Campaign helped close a gaping toxic loophole. The campaign virtually eliminated the largest source of arsenic exposure to most Americans—pressure-treated wood—the kind of wood used in playground equipment.

The Arsenic-Free Playground campaign virtually eliminated the largest source of arsenic exposure to most Americans—pressure-treated wood—the kind of wood used in playground equipment.

BILL WALSH – HEALTHY BUILDING NETWORK

In collaboration with:

Environmental Working Group

Clean Water Action

A Three-Pronged Strategy

1

We reframed the issue as a matter of child welfare, and worked with the Consumer Product Safety Commission, where the threshold for action on toxics was lower than at the EPA.

2

We targeted the vulnerable points in the supply chain – the few companies that mix and distribute arsenic compounds and two big-box retailers who sold most of the arsenic-laced lumber used in playground and home decks.

3

We recruited partner organizations that had the clout, infrastructure and consumer reach we needed to generate broad general news coverage that made people care about our cause.

Playing with Poison

Busy decision makers require clear choices for replacing furniture products with ones that meet Harvard’s health standards, as well as the community’s aesthetic standards. Henriksen and her team knew they had to devise a plan with clear guidelines that would make it easier for people to change their behavior.

As a first step, they updated the University-wide Green Building Standards in 2014 to include healthy material requirements and facilitate the disclosure of health and environmental impacts of products that are used in capital projects. That same year, Harvard issued its first Sustainability Plan and included Health and Well-being as one of its five areas of focus.

The key concept in the campaign was that America’s children were exposed to dangerous levels of arsenic through contact with pressure-treated wood used in playground structures and home decks. They were literally playing with poison.

Arsenic’s common use is in agricultural pesticides, and some lumber is pressure treated with arsenic compounds to prevent insect damage. Parents who hide the bug spray for fear of poisoning their children were sending them out every day into direct contact with similar toxins.

The Environmental Working Group and Clean Water Action both signed on, giving Walsh added clout and consumer reach, but arsenic was not on the radar at most other organizations.

Walsh admits he had a head start in targeting arsenic. “Nobody is going to defend arsenic,” Walsh says, “except the people who make it, and they had alternatives.” Even so, he had trouble assembling the coalition he needed to get traction at the grassroots level. The Environmental Working Group and Clean Water Action both signed on, giving Walsh added clout and consumer reach, but arsenic was not on the radar at most other organizations. “It just wasn’t a priority on anyone’s agenda,” Walsh says.

Finding Allies for Action

But Walsh had moved the arsenic issue out of an industrial regulatory debate into an intimate, emotional conversation about family health. He had clearly targeted pressure points: there were few sources of the arsenic; only three companies made the chemical infusion; only two major big-box retailers moved most of the treated wood into the marketplace, and public opinion was on his side.

Both of his partner organizations had huge mailing lists of concerned consumers. The Environmental Working Group had its offices in California, where environmental health was a hot topic.

Clean Water Action had offices across the country and could command local volunteer actions to create a sense of urgency and importance. They generated a grassroots campaign in news media that resulted in a broad consumer response. They forced the authorities to face the danger to children.

Victory Came Quickly

Soon, Walsh says, “Public opinion was going against all of them. The companies didn’t want to debate the question any more in the press.” The EPA felt the wind shift and closed the loophole that allowed arsenic easy access to U.S. products. With the consumer watchdogs on guard, the big-box stores began buying arsenic-free lumber. As Walsh had anticipated, that made a market for the three companies who pressure treat the lumber, and they switched to their equally profitable non-arsenic alternatives. The economics of pressure-treated lumber remained robust.

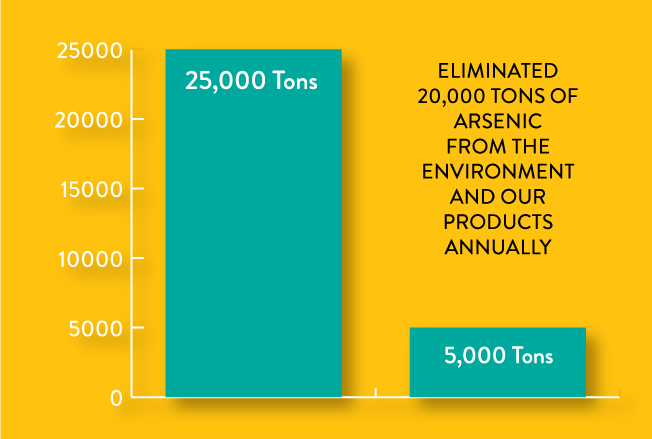

Measuring the results was easy. Almost all of the available arsenic came from a few importers. Federal law required the shipments to be tracked, so statistics were on record and open to view. Before Walsh, the statistics read “25,000 metric tons.” After Walsh’s campaign, the bottom line read only “5,000 metric tons.”

The RESULTS!